- Messages

- 1,509

- Points

- 40

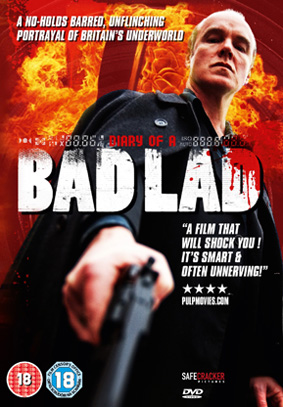

An article by Salford Film Festival Director Steve Balshaw about the state of British Cinema and the rise of micro-budget filmmaking. This is included on our site because Diary of a Bad Lad and Pleased Sheep Films get a prominent mention. This was originally published on various film websites around the web. One such website was britflicks.com.

If there is one dominant characteristic of modern British cinema, it is lack of ambition. How often have you seen the following straplines on a film poster: “The Best British Film of the Year” or “The Funniest British Comedy of the Year”? The word “British” in such a context, far from being an appeal to cinematic patriotism, is basically a qualifying adjective, carrying the underlying meaning “mediocre by international standards, but quite good if considered in isolation”. It is a warning not to get your hopes up, to keep your expectations low, in which case you may be pleasantly surprised. Francois Truffaut famously decreed that British Cinema was a contradiction in terms. While one might point to filmmakers as diverse as Michael Powell, Alfred Hitchcock, Nic Roeg, and Peter Greenaway to disprove this, all were mavericks, who were ultimately forced to seek work abroad. The British Film Industry as a whole seems purpose-built to prove the truth of Truffaut’s claim; isolating and driving away its talent, both maverick AND mainstream, while encouraging and rewarding mediocrity and lack of vision and ambition. All of our top filmmaking talents leave, because there is so little for them to do here. The reason for this is simple: we don’t actually have a British Film Industry any more. We have become merely a subsidiary of the American Film Industry. The most successful British Film Production Company, Working Title essentially create and package films for the US market, and to be fair they are very good at it. And, since they are the country’s market leaders, where they lead, others tend to follow.

The British Film Industry thus now has no interest in building a native industry that focuses on the UK and Europe. It is entirely focused on cracking America. And because it looks to American models to determine how it may do so, it puts its faith in Development. This arcane process sees British films endlessly reworked and rejigged, stripped of culturally-specific references, identity, and fundamental content in an attempt to make them more “universal” (ie American). Thus, Shane Meadows’ ONCE UPON A TIME IN THE MIDLANDS mutated during “development” from the low-budget Nottingham-based, modern revenge Western he’d originally envisaged into a messy low-brow farce filled with “name” British actors who had some supposed market recognition: Scotsman Robert Carlyle, Welshman Rhys Ifans, Scouser Ricky Tomlinson, Cockney Kathy Burke. All fine actors, but none of them, of course, from anywhere remotely near Nottingham: Such minor details are considered irrelevant when you are pitching at an American audience whose knowledge of the UK is gleaned entirely from Richard Curtis movies.

But at least ONCE UPON A TIME… got made in some form. Many films never make it beyond the development stage. Somehow the fact that they have been “developed” is seen as achievement enough.

This results in the kind of farcical activities practiced recently by a certain regional screen agency. Filmmakers were encouraged to submit scripts which might be developed into viable short films. As usual there were myriad hoops to jump through and quotas to fulfil, but in the end the submitted scripts were winnowed down to a half-dozen or so. The various writers / filmmakers were assigned mentors from a Script Development company in London, who offered notes, feedback, etc. And that was as far as it went. NONE of the films were actually made. So what exactly was the point of the exercise? Clearly not to encourage film production in the region. Presumably, though, it made some money for the Script Development company, and ticked a few boxes for the Agency.

Sure, short films do get made, even financed, through the RSA in question. Budgets in the past have ranged from £5K to £10K for a single short, and most of the films made have been set in one room, with money being spent on “name” actors (ie, they’ve been in HOLBY CITY or THE BILL) and 35mm film to shoot on. A filmmaker friend of mine recently said, given that amount of money he could - and would - make a full-length feature film. (He’s already worked out the budget, if anyone out there is interested.) His attitude is not uncommon in the North West. The Can-Do mentality is hardwired into the region’s populace. The only Film Production Company ever to make a success of it outside of London was John E. Blakeley’s Mancunian Films, which ran for over 30 years, from the 20s to the 50s, creating region-specific cinema. In the 1980s, local cult hero Cliff Twemlow was one of the first people to see the commercial potential of making cheaply produced films for the straight-to-video market. Both men were driven by the attitude that they didn’t need permission or approval from some company in London. They could make films if they wanted, and in doing so, they would find their own market.

This attitude persists in a new wave of local filmmakers working in the region. Struggling with miniscule budgets, dependent on favours, in-kind support, self-belief and shared enthusiasm, they do not have the luxury of dedicated month-long shoots and endless post-production. They are often working on the hoof, in their spare time, taking on other jobs just to pay the bills. Their films may take months, even years to complete. And working within such an extended time frame, they need to be able to sustain their faith in the project, and that of everyone else involved, or the whole thing would simply fall apart. Luckily, they have that faith and the drive that goes with it. And having made feature length films, usually for no more than a couple of grand and a hell of a lot of hard graft, they are not about to be told they should’ve spent more time in Development, that their films are not commercially viable in the modern film marketplace. They have come so far, and if need be they will find their own means of distribution and exhibition as well.

Leading this charge is DIARY OF A BAD LAD, Pleased Sheep Productions’ ferociously intelligent study of the media’s obsession with and complicity in modern criminality. Making its low budget work in its favour, the film is a faux-documentary about Northern Gangland, in which the filmmakers play fictional versions of themselves - young filmmakers just out of university, enlisted by their former tutor for a project that all of them see as a ticket to that much-coveted media job. Blurring the boundaries between the real and the reconstructed, the film is shot entirely documentary style, with scenes actually cut together from much longer in-character interviews conducted by the various actors and non-actors alike. So authentic is the film’s recreation of the modern documentary style, and so plausible is its gangland milieu, that when lead actor Joe O’Byrne appeared in character as the gangster Tommy Morghen to introduce a screening at the BBC in Manchester , somebody actually called security. The film has developed something of a cult following in the region, and has already been picked up by a number of international film festivals, but finding distribution has been an uphill struggle.

Joe O’Byrne is also one of the key players in Albino Injun’s LOOKIN’ FOR LUCKY, which he wrote and also appears in, together with many of his BAD LAD co-stars. This multi-strand portmanteau piece, deftly directed by Chris Leonard, offers a warts-and-all portrait of one day in the life of a run-down Northern housing estate; a day that will be a turning-point - or a crisis-point - for many of the estate’s inhabitants. The film’s stories are regionally-located, but universal, and its portrait of modern Britain is sharp and clear. Narratives run the gamut from comedy to tragedy, from moments of self-actualisation to those of self-ensnarement. And there’s a cute missing dog, for all the animal lovers in the audience to fret over. Were I pitching this to those shadowy, sinister types in Development, I would describe it as SHORT CUTS meets SHAMELESS, but the film began life before Paul Abbott’s acclaimed series arrived on TV, and has an edge all its own and a warm-heartedness which the oft-cartoonish SHAMELESS sometimes lacks. It does, however, have the structural ambition of SHORT CUTS, and like Altman’s film refuses to offer easy resolutions and pat conclusions. The premiere packed out the cinema, and the film could prove a real crowd-pleaser, were those crowds in a position to see it.

Honlodge Productions’ 25Gs offers, on the surface, a more conventional approach to gangland than BAD LAD; all tough-talking mob bosses and debts that need paying off in blood. But this surface is highly deceptive. The film seems initially realistic in style, with low-key naturalistic performances, but as the narrative progresses, dialogue and performances become increasingly stylised, sometimes deliberately jarring, seeming at times to draw attention to their very artifice. And gradually, it becomes clear that this is not really a gangster film at all. The film’s gangland milieu is merely the vehicle to deliver an elliptical Buddhist parable about action and consequence. Narrative trajectory folds back on itself, to show the fragile string of coincidence and casual decision-making which determine one sequence of events over another. The film is a bold experiment, flawed, perhaps, but fascinating, and marks Producer / Director Baldwin Li and writer Andy Hall as talents to watch. And it is precisely the kind of challenging, offbeat film that would NEVER have made it past the development stage, had they gone the conventional route in trying to get it made.

The most recent addition to the North West New Wave is Siab Studios’ micro-budgeted MANCATTAN. Very much a case of seizing the day, and making best possible use of a trip to New York, the film offers a postmodern Manc spin on the romantic longing and nerdy self-pity/self-aggrandisement that characterise the films of Woody Allen - specifically MANHATTAN, as the title suggests. But the film's approach is interesting, and has certain elements in common with BAD LAD: MANCATTAN, too, stars the film's own creative team, and blurs the boundaries between the real and the fictional. But whereas BAD LAD exposes the moral emptiness of the "true crime" doc, this takes on the RomCom(!) The film's writer-directors, Phil Drinkwater and Colin Warhurst play (fictionalised versions of) themselves: two former film students, now working in jobs they don't really like. One is facing commitment difficulties, the other pines after a female friend. Fleeing their troubles at home they go to Manhattan to make a documentary about Woody Allen. Here they bicker and philosophise about life, work, and romance, and finally achieve some kind of resolution. The initial cut, which I saw at a preview screening, had perhaps a bit too much “student humour”, and was a little overlong, but it has real heart, sharp, naturalistic dialogue and performances, and there's a definite voice there - and it's not Woody's! The film is currently being reworked slightly in response to audience feedback, and Colin promises the second cut will be “much zippier”. It should be well worth catching if you get the chance. Again, these are talents to watch and to nurture. They have the right attitude to go the distance.

What characterises all of these filmakers is their ambition. Each has refused to be hampered by their small budget, but has instead found ways to make it work to their advantage. Each has discovered that nothing focuses creativity more effectively than lack of money; and that when something is a struggle to achieve, it had better be worth achieving. So they got off their arses, in true Punk Rock style, and they went ahead and did it.

So - how do you get to see these films?

Good question.

These disparate filmmakers are out there, pounding the pavements, metaphorically and quite literally, marketing and distributing themselves; hiring screening venues out of their own pockets in the hope of recouping on ticket sales, seeking the support of film festivals and small independent cinemas who might be willing to take a chance on something out of the ordinary, even researching online means of distribution. They are working together and separately, leaving no pathway to exhibition unexplored as they fight to get their films seen. What does the future hold for them and for the films they have made - not to mention those they hope to make in the future? To answer this, we must consider the future of cinema exhibition itself. As the Multiplexes, and even the smaller independent and Arthouse cinemas become increasingly dominated by big studio product, as the advent of prohibitively-expensive digital projection threatens to bury the independent sector altogether, I predict the development of a two or even three tier system of cinema exhibition: The Multiplexes, screening endless big budget blockbusters from a server somewhere in America; those few smaller Arthouse and rep cinemas able to secure funding to install a digital projection system screening mainstream independent and foreign language films; and the rest - a rag-tag army of small theatres, galleries, clubs and bars, screening less mainstream, lower budget, more obscure work, from Beta and Mini DV at best, but most commonly from DVD. The process is already underway; the demarcation lines are already being drawn up. The number of short film screening nights popping up in clubs and bars up and down the country is no coincidence. It’s a collective reaction, a final rallying cry.

With dark days ahead, there is at least some slight ray of hope. We may be seeing here the birth of a defiant New Underground Cinema, seeking to reclaim the art of film from the marketing men and branding consultants, the script developers and intellectual property lawyers who have done so much to neutralise it. Catch it now, before the mainstream buys it all up, sanitises it, and sells it back to you with a Beyonce Knowles soundtrack and a McDonald‘s promotional compaign attached.

Last edited by a moderator: